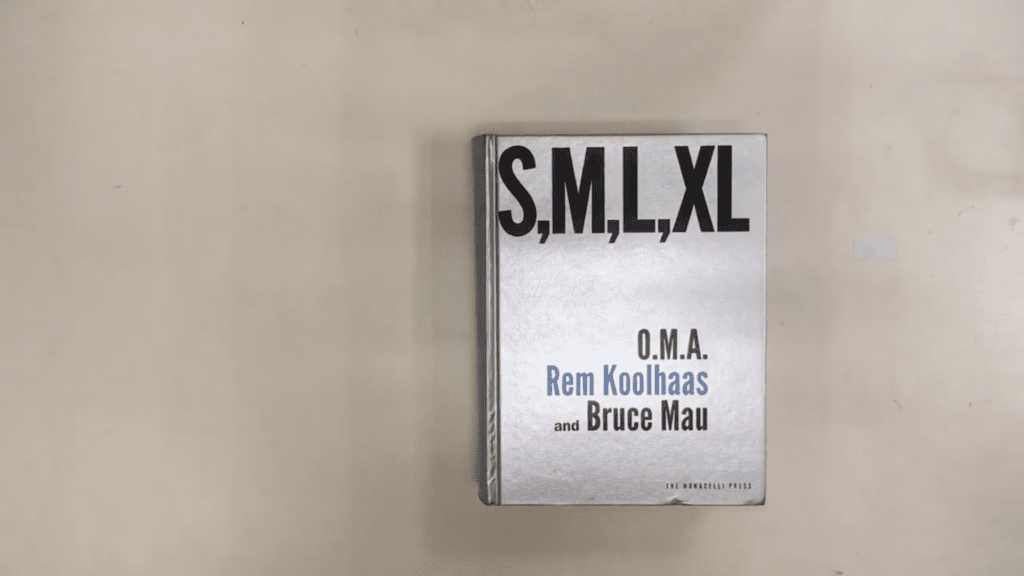

It was with the monumental book project S,M,L,XL that he officially achieved co-author status, along with architect Rem Koolhaas. That book was the design publishing sensation of the ‘90s, not only selling out its first run of 30,000 copies, but also its second printing of 70,000. For any book, that’s huge. For a 1,300-page design book, it must be some kind of record.

Bruce Mau

Across more than thirty years of design innovation, Bruce has worked as a designer, innovator, educator and author on a broad spectrum of projects in collaboration with the world’s leading brands, organizations, universities, governments, entrepreneurs, renowned artists, and fellow optimists.

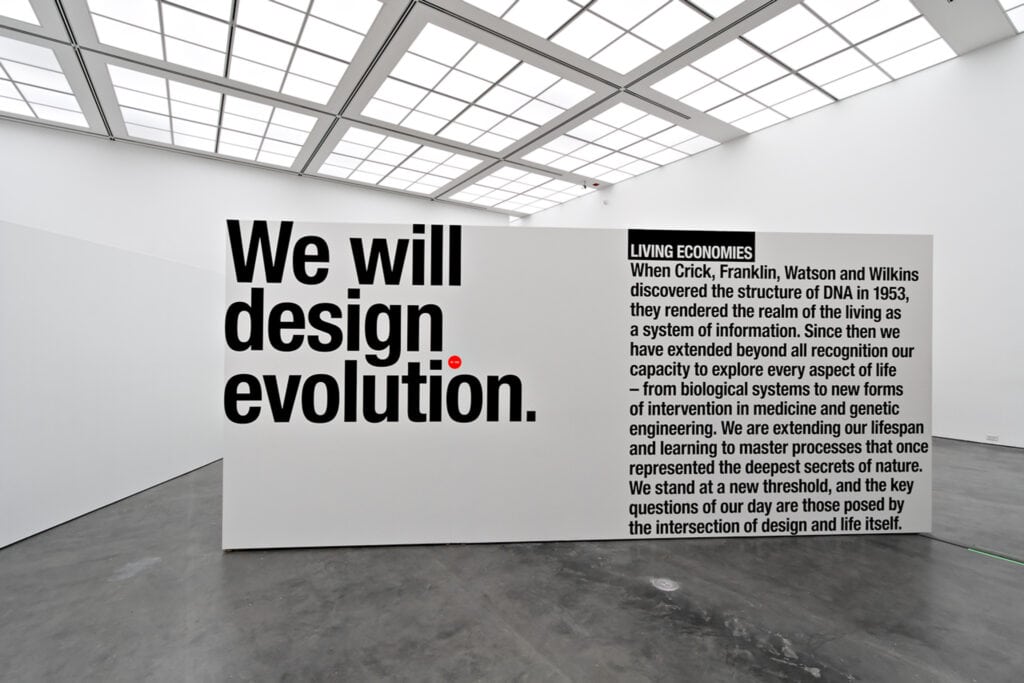

S,M,L,XL put Bruce’s reputation on a global trajectory for which there is still no apex in sight. In fact it seems to have more momentum now than ever. That’s because Bruce has managed to transcend the confines of graphic design to embrace a much bolder agenda, one which posits design as a core human capability that can and must be engaged to solve the world’s most wicked problems

Perhaps Bruce’s greatest gift is his irrepressible optimism. As he says in MC24, given the existential challenges we face as a species, we have no choice but to be optimistic. His optimism is bolstered by an unwavering belief in what he calls ‘life-centred design’ – a holistic approach that goes beyond ‘human-centered’ to consider all of life when making design decisions about our future.

Will Novosedlik on Bruce Mau

In the early 80s, when I was in the early stages of my own career as a graphic designer, I heard of a small outfit called Public Good. I called one day, out of curiosity, to learn more about the firm and its practice. I learned it was on a mission to work solely for non-profit organizations. One of the founders of that firm was Bruce Mau.

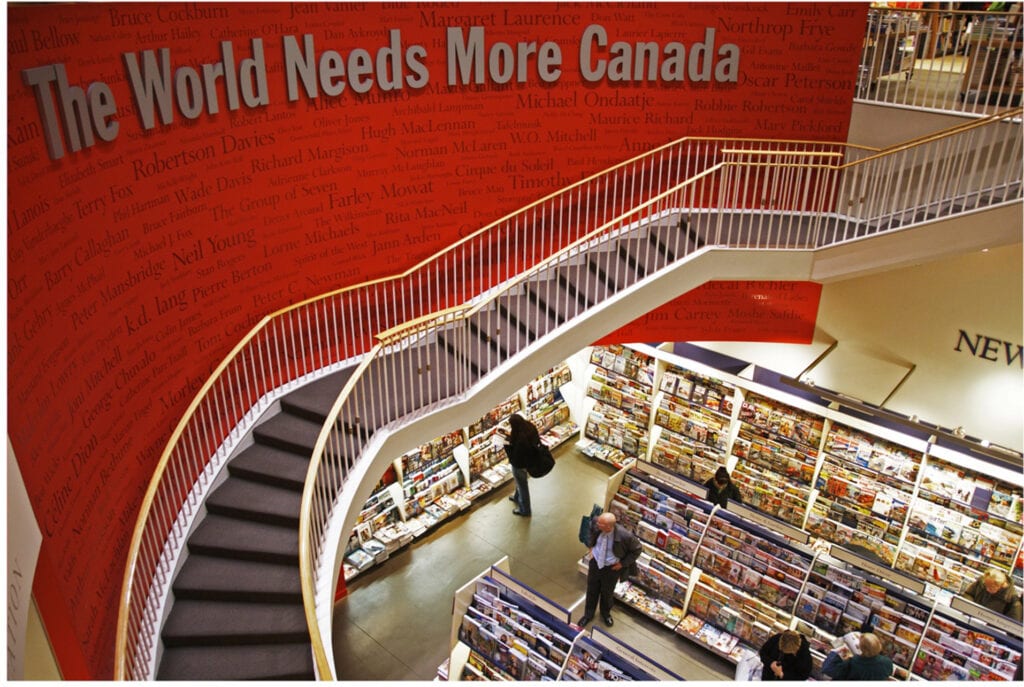

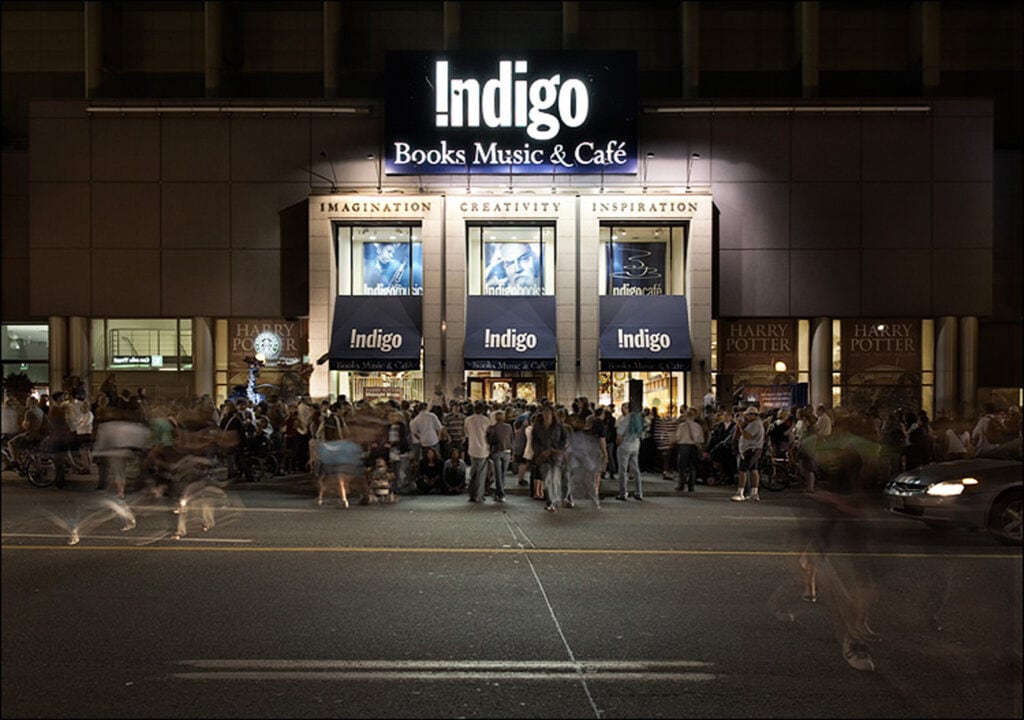

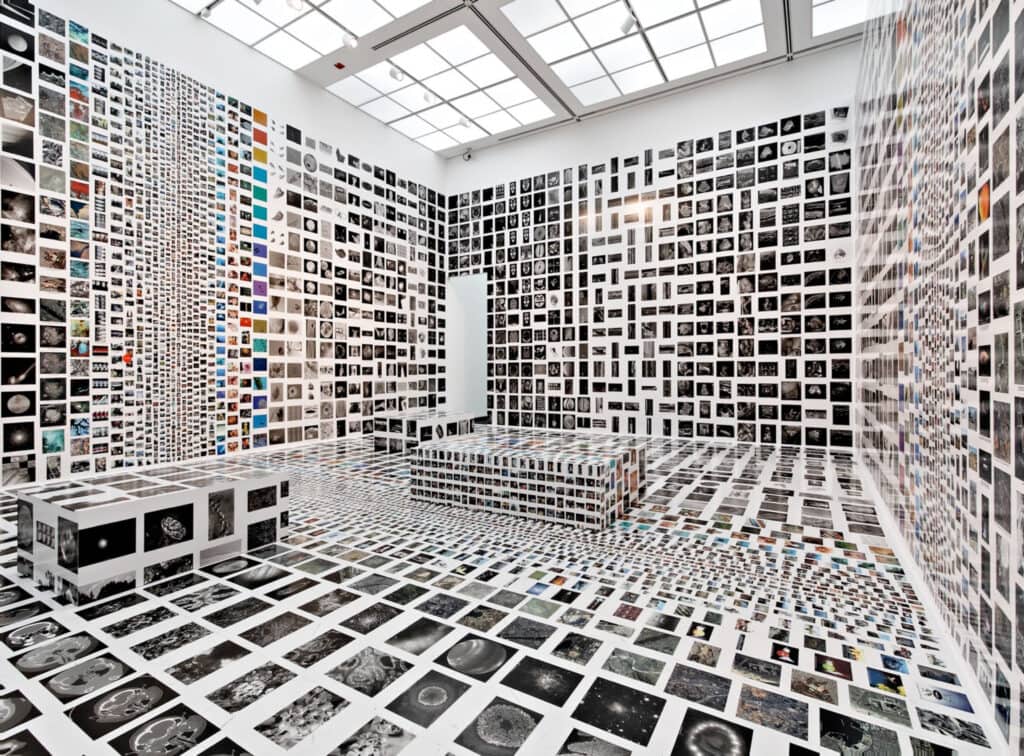

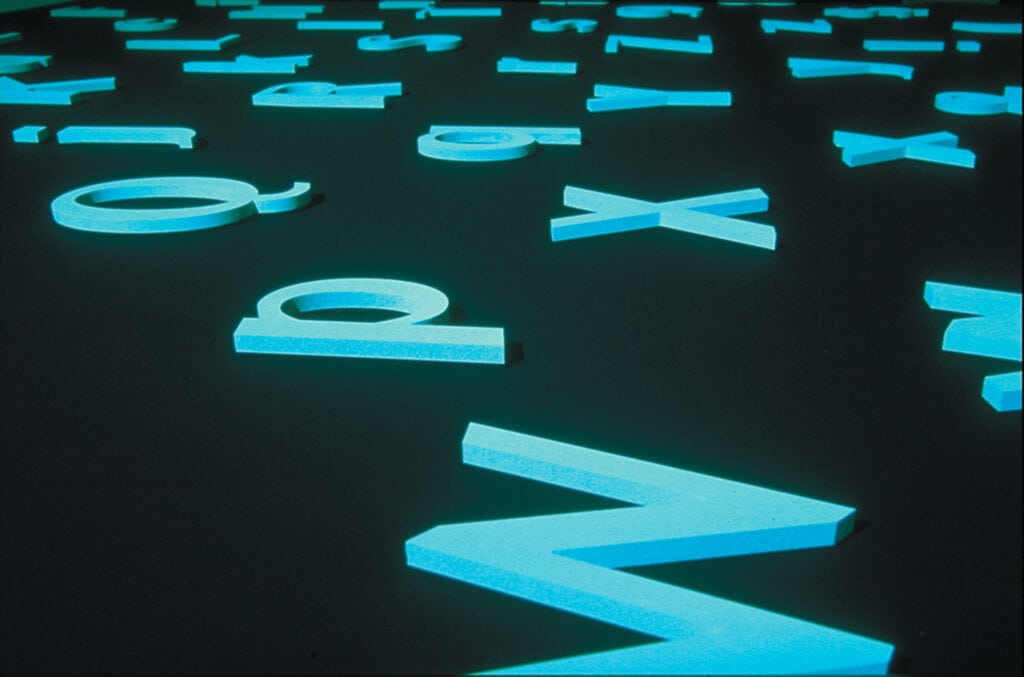

The next time I encountered Bruce, in 1993, he had left and was engaged in designing the now famous Zone series of publications. These were collections of essays that lived at the intersection of architecture and philosophy, and in their pages one could discern some of what are now the hallmarks of Bruce’s graphic style. But what really marked him was his ability to engage deeply with very challenging intellectual content. With the Zone series, the contours of Bruce’s ambition were becoming clear. Here was a designer who was neither interested in chasing trends nor in adopting, as most of his peers did, a ‘karaoke’ pose, always singing someone else’s song. It was with the monumental book project S,M,L,XL that he officially achieved co-author status, along with architect Rem Koolhaas. That book was the design publishing sensation of the ‘90s, not only selling out its first run of 30,000 copies, but also its second printing of 70,000. For any book, that’s huge. For a 1,300-page design book, it must be some kind of record. S,M,L,XL put Bruce’s reputation on a global trajectory for which there is still no apex in sight. In fact it seems to have more momentum now than ever. That’s because Bruce has managed to transcend the confines of graphic design to embrace a much bolder agenda, one which posits design as a core human capability that can and must be engaged to solve the world’s most wicked problems. When the City of Mecca asked him for a 20-year plan, he responded with a 1,000-year plan. For the Netherlands Architecture Institute’s visual identity he designed a hundred versions of the logo and provided a palette of 1,000 colors. S,M,L,XL was 1300 pages. His other books – Lifestyle, Massive Change, MC24 – run to 500+ pages. It’s that kind of audacity that has earned Bruce both the awe of his admirers and the ire of his critics. Perhaps Bruce’s greatest gift is his irrepressible optimism. As he says in MC24, given the existential challenges we face as a species, we have no choice but to be optimistic. His optimism is bolstered by an unwavering belief in what he calls ‘life-centred design’ – a holistic approach that goes beyond ‘human-centered’ to consider all of life when making design decisions about our future. Bruce would merit receipt of the Les Usherwood award on the strength of his graphic design work alone. But he and his partner Bisi Williams have turned their practice into a tireless appeal for all of us to recognize design’s critical role in creating a future we, and every other life form on earth, can live in. His work is an invitation – nay, a challenge – to take responsibility for the power we all have as designers and join in this vital mission.